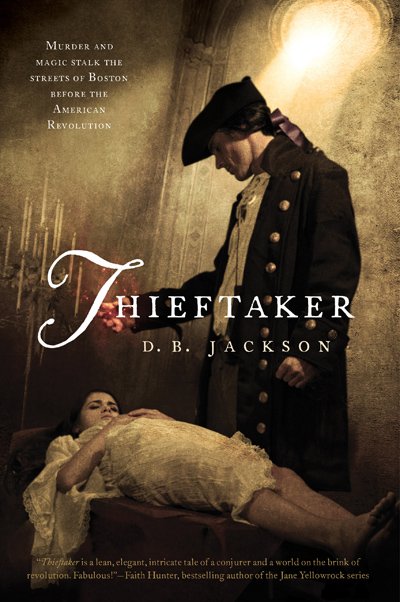

I’m pleased to have author D. B. Jackson here today to talk about his new historical fantasy mystery release, THIEFTAKER, set in colonial Boston.

By the way, this is what I said about the novel: “Thieftaker is an excellent blend of mystery and magic set in the turmoil of Colonial Boston as revolution brews and political factions collide. The setting is vividly painted, and the story is a fine portrait of a man caught between his bitter past and its legacy, and the constant dangers and reversals that dog his attempts to build a new life for himself.”

Did you know that throughout his adult life, Samuel Adams was afflicted with a mild palsy that made his head and hands tremble? I hadn’t known either.

Did you know that women in Colonial Boston — and other North American cities in the second half of the 1700s — enjoyed a good deal of financial and social independence, and that it was not at all uncommon to find single women, usually widows, running their own shops and taverns?

How about this one: Did you know that in the 1760s, at least until the British occupation of the city began in the autumn of 1768, Boston had only one law enforcement official of consequence? It’s true. His name was Stephen Greenleaf and though he was Sheriff of Suffolk County, he had no officers at his command, no assistants to help him keep the peace, save for the men of the night watch who were almost universally incompetent, or venal, or both.

My newest book, THIEFTAKER, which was released by Tor earlier this week, is the first book in a historical urban fantasy series set in pre-Revolutionary Boston. The series follows the adventures of Ethan Kaille, a conjurer and thieftaker, as he solves murders and grapples with the implications of the deepening divisions between the colonies and the Crown. I have a Ph.D. in U.S. history, and though I often used my history background in the worldbuilding I did for my earlier fantasy novels, this is the first project I have undertaken that allowed me to blend fully my interest in history and my love of fantasy.

Not surprisingly, I had to do a tremendous amount of research for THIEFTAKER, its sequel (THIEVES’ QUARRY, Tor, 2013), and several related short stories. And one of the things that struck me again and again while I was reading through documents and monographs, was that so much of the past is lost to us in the glare of Important Events and Important People. As Kate put it to me as we were exchanging ideas for this post, “What about the history that isn’t taught?”

By way of example: THIEFTAKER begins on August 26, 1765, a night when a mob of protesters rioted in the streets of Boston to vent their frustration at Parliament’s passage of the Stamp Act. (In the book, the riots coincide with a murder that Ethan has to investigate. But I digress.) The homes of several British officials were ransacked, most notably that of Thomas Hutchinson, the Lieutenant Governor of the Province of Massachusetts Bay. Hutchinson blamed James Otis and Samuel Adams for much of what happened that night, viewing them, with some justification, as the leaders of the growing rebel movement. But one name you almost never find in history textbooks is that of Ebenezer Mackintosh. Great name, right? You might think that a man with such a name would attract some historical attention, especially when you learn that he was the leader of the mob responsible for so much destruction and subsequent political upheaval. But though as a co-called “street captain” he had a strong following among laborers and unskilled workers in Boston, he was never “important” enough in more formal political circles to draw the attention of scholars. That said, he does play a crucial role in THIEFTAKER, as do Samuel Adams and Sheriff Greenleaf.

In addition to learning about some of the people who don’t usually find their way into “taught” history, I also learned a tremendous amount about the city of Boston itself, including the ways in which city officials sought to adjust to circumstances as population centers grew, making urban life more complicated. During the middle decades of the eighteenth century, Boston experienced a number of devastating fires, not least among them the Great Cornhill Fire of March 20, 1760. This fire began at a tavern called the Brazen Head and swept through the South End down to Boston Harbor, destroying three hundred forty-nine buildings and leaving more than a thousand people homeless. Miraculously, no one was killed. (I should note here that I have written a short story about this event — “The Tavern Fire” — which appeared in the AFTER HOURS: TALES FROM THE UR-BAR anthology edited by Joshua Palmatier and Patricia Bray. The story can now be found at the D.B. Jackson website.

The spate of fires that struck Boston changed the cityscape. After Boston’s Town House burned to the ground in the fire of 1711, the new one — the now famous Old State House — was rebuilt in brick. In the aftermath of the 1760 fire, city leaders passed an ordinance mandating that all new construction in Boston be done in brick or stone rather than wood. Faneuil Hall, which was destroyed in the Cornhill fire, was rebuilt in 1761 in its present form, again in brick. Moreover, noting that attempts to combat the blaze were hampered by lanes that were too winding and narrow, city officials also decreed that several of the smaller lanes in the Cornhill section of the city be widened and straightened. As a result of the fires, Boston in 1765 looked far more like a modern city than it had only half a century before and by the end of that year, many of the landmarks we associate with Boston were already in place.

Finally, to bring this discussion full circle, I should add that in the aftermath of the Cornhill fire, one of Boston’s tax collectors refrained from demanding payment from those citizens most grievously affected by the catastrophe. He had no permission from his superiors to do this, but he felt that those most in need should be relieved from having to pay. His name? Samuel Adams, of course. As it turns out, Adams might have been a political genius, but his personal finances were a mess. Several times, he almost lost his home at auction because of his personal debts. And his poor relationship with money extended to his early public service. In the early 1760s, a committee of the town meeting did an audit to determine why the city of Boston suddenly found itself in a financial crisis. The audit determined that tax collectors had failed to bring in some four thousand pounds owed by the citizenry. Adams alone was responsible for more than half of the shortfall.

These lesser known historical facts are more than entertaining. They are tiny gems that make a historical narrative sparkle, that add depth and flavor and richness to a historical setting. Getting the details right on things like the Stamp Act and even the riots that took place the night of August 26, 1765, was relatively easy. Over the years, much has been written about those topics. But the “untaught” history, the small details that are harder to find, are also the ones that catch readers by surprise, that draw them deeper into both character and story. And, I have to admit, they are also the rewards of historical research that I value most. After all, readers aren’t the only ones who need to be entertained; this should be fun for us writers, too.

*****

D.B. Jackson is also David B. Coe, the award-winning author of a dozen fantasy novels. His first book as D.B. Jackson, Thieftaker, volume I of the Thieftaker Chronicles, will be released by Tor Books on July 3. D.B. lives on the Cumberland Plateau with his wife and two teenaged daughters. They’re all smarter and prettier than he is, but they keep him around because he makes a mean vegetarian fajita. When he’s not writing he likes to hike, play guitar, and stalk the perfect image with his camera.

I knew a little bit about Adams thanks to McCullough’s Biography of him, but a lot of the other things you’ve learned are new to me.

Our view of history is through a dim flashlight, and illuminating all the corners of history with that flashlight is hard work indeed. But rewarding for a writer, when they can bring their illuminations to life with the power of Story.

Paul, I loved McCullough’s biography of John Adams, but this was actually Samuel who had the palsy and who appears in the book (despite what one professional reviewer said!). But yes, your flashlight analogy is spot on. I think that historical fiction is a great way of getting people more interested in history, though I also think that the illumination of corners is best left to scholars and non-fiction history books.

Pingback: 2012 | I Make Up Worlds