Join Tessa Gratton and me as we read the Shahnameh by Abolqasem Ferdowsi. We’re using the Dick Davis translation (Penguin Classics).

Today’s portion: The Tale of Zal and Rudabeh

Summary: Zal, son of Sam, falls in love with Rudabeh, who is the daughter of Mehrab, himself the grandson of the demon Zahhak. Because of her relation to Zahhak, Sam and Manuchehr initially oppose the marriage, but a prophecy that Zal and Rudabeh’s union will produce the most glorious son to protect Persia brings everybody around.

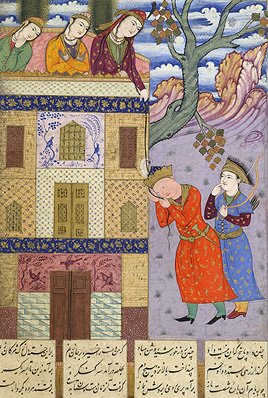

Zal stands with a companion at the base of a palace wall. He touches a lock of hair which Rudabeh, standing at the top of the wall, has let down. She has several companions with her.

KE: Where to even start? This sequence is so filled with rich storytelling that it could be an entire novel.

Years ago I read that “romantic love” is a modern invention, so I always enjoy reading stories like this that put the lie to that notion. It took me a bit to figure out what the obstacle was in the relationship: that Rudabeh is Zahhak’s descendent and thus deemed unsuitable.

Another thing that fascinates me about this tale, besides Ferdowsi’s endlessly inventive language, is its structure. If I had worlds enough and time I could write an entire essay that is about how conversation and consultation frame the various stages of the story. The young couple’s journey to matrimony is a series of social interactions with the powerful people (their parents and their king) around them. Rudabeh’s interactions are more personal and private than Zal’s, which are more public, and it is interesting how Sindokht shifts between the private and public spheres.

My favorite episode is probably that of Rudabeh’s three slave girls who seek out and converse with Zal. They are clever, confident, and free to speak. For one thing it shows that Western cliches about what women could and couldn’t do in “Eastern” societies are just that: cliches. This is borne out later when Rudabeh’s mother, Sindokht, takes charge of the expedition to travel to Sam and convince him to spare their kingdom from Manuchehr’s (presumed) wrath and to allow the young couple to marry. She states “I own castles and palaces, treasures, and slaves.” Later Sam gives her a whole raft full of rich treasure. The idea of helpless, passive women languishing in the harem . . . . nope.

The element of women’s agency is also shown in Rudabeh not only sending out her three trusted women to contact Zal but arranging for him to meet her in her palace (she has her own palace). I don’t know about you, but I read the sequence as she and Zal having sex. The idea of virginity has yet to be linked to female value. Certainly the sexual activity of the two sisters who were married to Zahhak is immaterial when they then marry Feraydun, and there is absolutely no indication that any notices or cares what the love-struck Zal and Rudabeh might have gotten up to beyond a few coy and amused references to the men Zal speaks with being aware that all he can really think about is HER. I guess one could argue that they keep it secret and so no one knows, but that doesn’t seem to be important.

This aspect is all very refreshing.

True love triumphs! With a little help from an intelligent mother, loving but anxious fathers, and astrology.

And then right in the middle of the fraught negotiations to calm Manuchehr and allow Zal and Rudabeh to marry, we get the incredible story of Sam fighting “the dragon that emerged from the River Kashaf.” This remarkable episode is merely a brief plot point along the way, brought in as part of a letter to convince the king.

What a great story this is.

TG: I loved this section, too, and Rudabeh’s mom Sindokht is my favorite! The part you pointed out about her owning her own castles and treasures and slaves really stood out, since I don’t think we’ve seen women explicitly owning things before, though Feraydun’s mom seemed to rule her own land and so it’s been implied. I loved that Sindokht is allowed her own internal world in addition to being the voice of reason several times and also negotiating with kings – she was so full of anxiety it appeared like bruises on her skin (I loved that line), and it was her sorrow that drew Mehrab’s attention, but she got up and acted smartly. Her relationship with her husband was very interesting to me, too, since they seemed to compliment each other like partners. He is so passionate and melodramatic (as many of the men are in this book), and looks to her for advice (as many of the kings have done with their wives), but it was ratcheted up to a new level when Mehrab was at his wits end for how to keep their country safe, and all he could think of was to kill Sindokht and Rudabeh to prove to Manouchehr that they don’t need to be enemies. He begged Sindokht to come up with a better idea. “Fight for your life” he said, and I think he desperately wanted her to find a way. He relied on it, even, and trusted her to do it. I’ll take more Mehrab/Sindokht please, especially since they’re descended from the demon. (Which was apparent in their struggles for how to behave, too, as when Mehrab immediately thought to make “a river of blood of Rudabeh,” just like his grandfather (the demon!) would have done.)(I just ship it completely: #sinrabforever)

Though I was entertained by the constant negotiations and the fact that this entire long section was all about the threat of violence and solved with talking, I have to admit I was thrown in the middle when Sam already knew about the prophecy for Rostram, but didn’t use that to convince Manuchehr. He eventually got there on his own, but it seemed like a purposeful muddling of the narrative, and problems that can be solved by simple revelation of information is one of my least favorite romance tropes. That said, it highlighted how little the story relies on withholding information like that in general.

I assumed they had sex, too, since they spent all night intwined. I’m not sure how else to read it, and I laughed out loud when Manuchehr told Zal to stop lying about missing his dad, “I know you just want to get back to your girlfriend.” <3 <3 <3

My other favorite line was

“He scatters gold when he’s at court, and when

He’s on the battlefield, the heads of men.”

NICE.

The vivid details of the dragon episode were fantastic – I’m thinking in particular of Sam emerging naked because all of his clothes had been burned off.

#

Next week: Rostam, the son of Zal-Dastan

Previously: Introduction, The First Kings, The Demon King Zahhak, Feraydun and His Three Sons, The Story of Iraj, The Vengeance of Manuchehr, Sam & The Simorgh

This sequence is so filled with rich storytelling that it could be an entire novel.

I concur. The sequence relating the story of defeating the dragon– you could get at least a novella out of expanding *that* alone.

“Where to begin?”

Couldn’t agree more! Also love #sinrabforever. 🙂

I’m also relieved to know that standardized testing and word problems are not a modern invention. 😉

I too fully accept that it was WHO was entwined not THAT they were entwined (I also noticed it was suggested that ZAL set snares!). I loved the rich flowery speeches, the constant reminders of how faithfully various overlords had been served and thought it was priceless when the priests threw the question back at Zal saying they weren’t nearly wise enough to answer it. haha, way to CYA. I also was really struck by how often astronomy (not just astrology) was used and referenced as common knowledge. I’ve always thought of the region as being historically rich in astronomical research but had thought of it as more specialized but this makes me think that much of that technical knowledge must have been common knowledge. I thought the elaborate wedding celebration might be a time we’d finally see Zal’s mom but it was not to be. I’d like to have seen her and Sindokht grinning about their palaces and kids.

I just could not stop getting caught up in the language and descriptions. I hope you’ll enjoy this list of a few of my favorites (ok, more than a few).

…the Pleiades are not as lovely as your face…

…like the contracted heart of a desperate man…

…gadding about… <– could not be more pleased that there is a Farsi equivalent to "gadding"

…loosened her hair, which cascaded down, tumbling like snakes, loop upon loop.

…which glittered like the planet Jupiter.

…his lips were cold with sighs…

…wind does not obey the dust.

…but do not burn the hearts of the innocent inhabitants of Kabol…

…had the gait of a pheasant.

…with his glittering sword / He'll make the air weep, and his food will be / A roasted wild ass, spitted on a tree…

…writing magical incantations to the sun to protect her.

…blushed like a tulip from head to foot…

And if this isn't romance I don't know what is: "…I burn in the fire of my love for her. In the dark night the stars are my companions, my heart seethes in turmoil like the sea, I am beside myself with grief, and all men weep for me. My heart has seen injustice but I breathe only to obey you."

(Is anyone else reminded of: You are my sun, my moon, my starlit sky; without you, I dwell in darkness?)

The language is just so inventive. Not for nothing is Persia known as a land of intense love for and respect for and praise for poets and poetry.

I also found it interesting how Zal and Rudabeh *heard* about each other first, became interested because of what they heard, and then arranged their clandestine meeting. After that they don’t see each other again until the triumphant ending. It’s fascinating because, again, it’s a narrative form we can understand on many levels but it is also doing some things very differently from what a modern USA narrative would likely do — they would have more meetings between the lovers, narrow escapes, and so on.

Everyone seems to want more about the dragon.

Rachel, did you just quote “Willow?” LOL

I never thought of the gait of a pheasant as something good before this.

random pointless facts: pheasant hunting used to be a thing around where I grew up in the Willamette Valley. I don’t think it still is. In fact, I don’t know if there are pheasants left there, which makes me sad.

TG – Yessssssssssssssss!!! 🙂 I love Willow. Every glorious and cheezy moment of it. A movie truly ahead of its time. The reception for fantasy film/tv is so different now than when Willow came out. (Which seems a bit of a Captain Obvious point actually.)

KE – Does that mean that you can confirm or deny the gait of a pheasant as a complimentary comparison? I’ve only ever seen pheasants in a museum aviary habitat and those were chicks. The adults were off adulting. The chicks were adorable but I didn’t get a good view of the gait. In fact, I probably wouldn’t have thought to notice. A missed opportunity for sure. (And very sad to think they may not still be in the Valley where you grew up.)

I would have thought the gait of a pheasant to be . . . birdlike, and mannered. So maybe that works?

Pingback: Sam & the Simorgh (Shahnameh Reading Project 6) | I Make Up Worlds

Pingback: The Beginning of the War Between Iran and Turan (Shahnameh Reading Project 9) | I Make Up Worlds

Pingback: The Shahnamah Reading Project 2016, with Tessa Gratton & Kate Elliott | I Make Up Worlds

Pingback: Rostam and Kay Qobad (Shahnameh Reading Project 11) | I Make Up Worlds

Pingback: Kay Kavus’s War Against the Demons of Mazanderan (Shahnameh Reading Project 12) | I Make Up Worlds