The ten mile long road from Yokosuka also served as the single street for the village of Kamoi, before dead ending at the Harbor Entrance Control Post. The population of the village was probably no more than 250 people. It occupied a shelf of land above the half-moon shaped bay. The beach itself was pebbly and served as a pull-out resting place for a few small fishing boats. Our boat dock jutted out into the south-east curve of the bay.

Some of the villagers farmed small plots of land scattered around on the few level spots available. Two women owned a barber shop where we got our hair cut and where we occasionally sold cigarettes. Once when getting my hair cut a little boy of about three came into the shop from the house in back and said something to his mother, the barber. She excused herself, knelt down and nursed him briefly before returning to finish my hair cut. It made an impression.

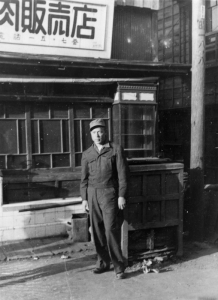

There was a small tea shop in town, a couple shops, including a meat store of which I have a photograph, with our electrician in front, and I seem to recall a shop which offered household items. Some of the Japanese who worked at HECP lived in town. It was in one of those homes where I met the girl from Hiroshima.

One night, when visiting a different home, my billfold somehow fell out of my pocket. As I walked home in the pitch black darkness a little boy caught up with me to return it.

The Japanese electrician, who served HECP after our Navy electrician left, lived in Kamoi with his family. That family included a young women. I visited them on occasion and even helped teach her (Kazuko) how to play ping pong in our recreation room. Once, after consulting a Japanese-English dictionary, she told me that I was a gentlemen. She gave me a white silk handkerchief when we left Toriga Saki. She gave two handkerchiefs to my friend, Merv, who told me that it was because he wasn’t a gentlemen. One remembers those things.

A Shinto shrine occupied a central spot along the road and included a resident Shinto priest. I talked to him on occasion, but he knew very little English. Once in a while he had prepared a question for me. Fifty-seven years later, in October 2003, an old woman resting on a bench at the shrine told me that the priest had died just six years earlier. The Shrine was unchanged except that it had been painted and cleaned up. The red fox in one corner was truly red.

My most memorable experience in Japan, the spring festival dress rehearsal at the Kamoi elementary school, is described in another essay in this collection. It was a small school, not many more than a hundred pupils and a handful of teachers, several of whom I met. I visited the school more often than any other single place in town, except for the barber shop.

As a postscript I would only add that when I visited Kamoi in 2003, I discovered that no significant changes had occurred along that coastline. For some reason, the government had prohibited construction projects of any kind along that stretch. I almost felt like I was in some kind of time warp.

Pingback: Remembering Japan: 1945 – 1946: Chapter Three | I Make Up Worlds

Pingback: Remembering Japan: 1945 – 1946: Chapter Four | I Make Up Worlds

Pingback: Remembering Japan: 1945 – 1946: Chapter Ten: Japanese Hot Tub | I Make Up Worlds

Pingback: Remembering Japan: 1945 – 1946: Chapter Five: Japanese Signalmen | I Make Up Worlds

Pingback: Remembering Japan: 1945-1946: Chapter Nine: A Social Call | I Make Up Worlds