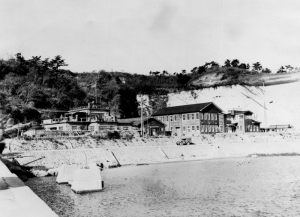

The Harbor Entrance Control Post was a signal tower. It was located at the very entrance to the Bay, some 50 miles east of the destroyed city of Tokyo. It was under the command of the Port Director who was a high ranking Naval Officer in charge of all ship traffic and dock facilities in the Bay. This included the harbors of Yokohama and Tokyo as well as the former Japanese Naval base at Yokosuka, where the Port Director’s headquarters were located. All those harbors were inside the Bay. The Signal tower was located just outside the Bay, on the east side of a point of land called Kanon Saki beside a tiny fishing village called Kamoi. The ship channel was no more than five miles wide. The far side could be seen from the tower.

HECP’s job was to communicate visually with all ships entering or leaving the harbor. There was certain information we required of every ship. Those leaving the harbor were asked about their cargo, their destination and their estimated time of arrival. This information and other information as required by Port Director, or volunteered by the ship, was then phoned or radioed to the Port Director’s office. Entering ships were also asked what they carried, from where they had sailed and where they would like to anchor. Further information was communicated to them as to where they should anchor or dock and also information about supplies etc. While it was a bit more complicated than that, those were the basics.

The signal tower itself was only two stories tall, hardly a tower, but that’s what we called it. The crew was housed on the first floor as were the officers in special quarters with a dining room where they were served meals. The crew ate in a mess hall, but were served by Japanese employees who were grateful for the employment.

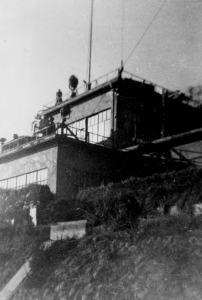

The second floor contained a covered and uncovered section. The glassed-in walled section gave a clear view of the harbor entrance and out to the horizon in the east. In it was located the office equipment, the telephone to the Port Director, a radio for back up work, desks, chairs, files, book shelves and an electric plate for making coffee. In front of that room was an outdoor flat area, surrounded by a railing for mounting 12 inch diameter signal lamps.

They appeared to be searchlights and could indeed be used for that. These, however, were equipped with a venetian-blind-like cover which shut out all light. They also contained a handle on the right side of the lamp which could open the shutter, thus emitting a beam of light. The shutters automatically closed when the handle was released. These lamps were aimed directly at the ship, and could, of course, continue to be aimed as the ship proceeded on its course.

We also had a very powerful signal lamp. I believe it was about 24 inches in diameter. It was mounted on a rail inside and could be rolled outside for use in foggy weather, or if we needed to communicate with a ship some fifteen or so miles away, on the horizon. We preferred not to use it. And we also had a 20 power set of binoculars mounted on a tripod. It was stored inside when not mounted. It made it easy to see blinking lights clear out to the horizon. It is also worth mentioning that HECP had been used before and during the war by the Japanese Navy in exactly the same way we were using it.

What remains to be said is something about Morse Code. That is the system we used to communicate. A short flash of light followed immediately by a long flash of light is an A, and so on through the alphabet. Each number had its own code also. Signalmen worked in pairs. One would read the message from the ship aloud. The other would record the message, but also serve as back up in case the reader had problems. They took turns.

How fast was the code sent? Standard Navy speed was 8 words a minute. That speed was required to become a rated Signalman. 10 words a minute was excellent. With constant practice and careful attention a truly skilled signalman could read 12 words a minute – especially if a buddy or two was hanging around and helping out.

This is how it worked: the tower would challenge a ship by sending two letter A’s. The ship would respond with the letter K – dash dot dash. We would then begin our message. After every word the ship’s signalman would send a dash of light, indicating that he had read the word. We would proceed. At the end of our message we would send K. If the ship had it all, it would send an R. We followed with an R and that was it. There was a wrinkle in all this, a rule of practice. No signalman was ever to send faster than he could read. It was like the eleventh commandment.

Now, we were crack signalmen. So instead of giving a flash after every word we read we just opened the shutters and left them open. This informed the ship’s signalman that we could read as well as any other signalman in the fleet. It was a smart alecky thing to do. But we were that good. And if there was any doubt we could have three to five signalmen on the tower helping out within a couple minutes.

We pulled that on the Battleship Missouri when it came into harbor once. Before it was over we had at least five signalmen reading — and the battleship’s crew were humbled. They had to ask for a repeat and we kept our light on the whole time. That’s how we earned our pay until we closed the station in May of 1946.

Pingback: Remembering Japan 1945 – 1946: Chapter Two | I Make Up Worlds

Pingback: Remembering Japan 1945 – 1946: Chapter Two | TiaMart Blog

Pingback: Remembering Japan: 1945 – 1946: Chapter Four: Work & Play | I Make Up Worlds

Pingback: Remembering Japan: 1945 – 1946: Chapter 4: Work & Play | TiaMart Blog

Pingback: Remembering Japan: 1945 – 1946: Chapter Eight: | I Make Up Worlds

Pingback: Remembering Japan: 1945-1946: Chapter Nine: A Social Call | I Make Up Worlds

Pingback: Remembering Japan: 1945 – 1946: Chapter Three | I Make Up Worlds

Pingback: Remembering Japan: 1945 – 1946: Chapter Ten: Japanese Hot Tub | I Make Up Worlds

Pingback: Remembering Japan: 1945 – 1946: Chapter Twelve: The “Singers” | I Make Up Worlds

Pingback: Remembering Japan: 1945 – 1946: Chapter Five: Japanese Signalmen | I Make Up Worlds

Pingback: Remembering Japan: 1945 – 1946: Chapter Seven: The Toriga Saki Fleet | I Make Up Worlds

I am throughly enjoying your dad’s writing. It makes me very nostalgic and can hear him selling the story. I’ve heard several stories about JC history and cherish the revelations that resulted. Thank you for sharing.

Michelle, thank you so much. I’m delighted to be able to offer his remembrances up online.