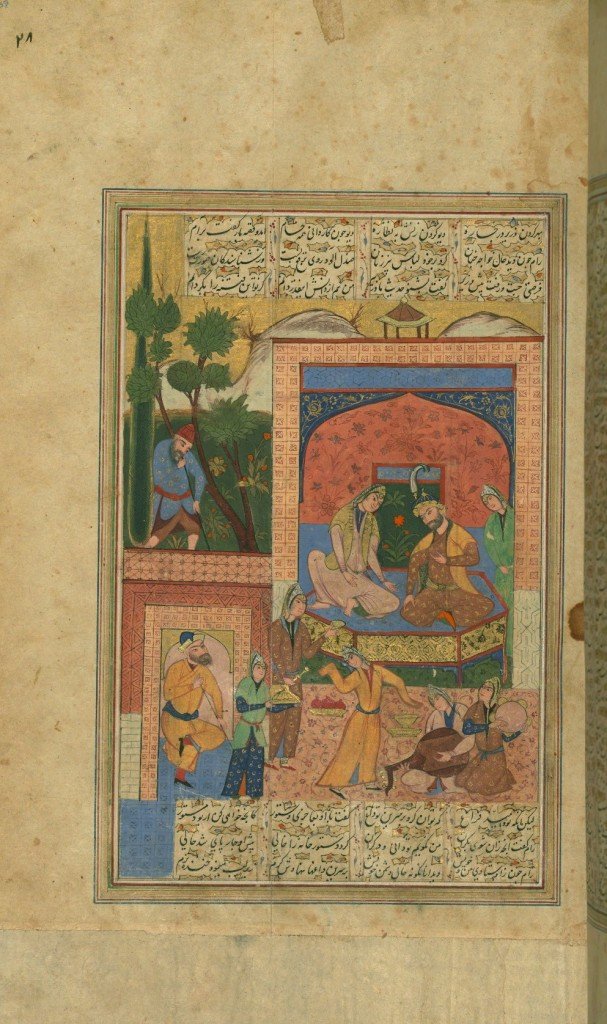

This week: The Reign of Bahram Gur

Synopsis: “Bahram Gur rules the world, has too much sex (arguable), impresses the King of India, and dies after giving away and spending all his money.”

TG: My parents joke about how we won’t have any inheritance from them because they plan to use all their saving traveling the world after retirement. That sounds fair to me, but when Bahram Gur basically does the same thing–to the point of having his vizier plan out how much money he has to spend when before he dies– it feels a little fishy.

That’s how I feel about this entire section. Many of the things Bahram Gur does are things Sekandar also did (like going to a foreign king in disguise) but the motivations seem less pure somehow. Maybe it’s just because he trampled that girl in the last section, and I can’t forgive him, but even his mischief comes off as less trickster like and more mean-spirited. He lies to the king of India (as well as multiple of his subjects) about who he is, and instead of being charming, it’s seedy. (At least one of these times he’d lying specifically to get into a girl’s bed, so again, unlike Sekandar, his motives are very suspect.)

I wish I knew more about when these stories were being made famous, and to what purpose, in order to tie them more directly to shifting culture, because it’s stunning how differently the women are treated in this section than before. They aren’t characterized with their own wealth in the same way, or their own lives and motivations. They’re just there to be taken by Bahram Gur to prove his stamina and greatness. Sometimes, they’re overtly used as symbols of their fathers’ wealth and status, instead of more complicated relationships I’ve grown used to.

We got almost as many horse names in this section as we did names for women.

Unlike previous episodes where kings and warriors defeat great beasts (the white demon, the worm) the rhino and dragon in this are again just props for Bahram Gur with no stories of their own.

Overall, it reads as a diminished version of the kind of complicated glory I’m used to. I’ve also noticed a lessening of the poetic language– fewer lines devoted to armies and the colors of war. We still get dramatic descriptions of wealth, but not the rest.

PS. I disagree heartily that once a month is a good amount of sex to have. But it’s the only thing I agree with Bahram Gur about.

KE: Like you, I am finding the shift into the historical to create a diminished story. The people aren’t as grand and heroic. The repetition of motifs has gotten more obvious, I think, as you say, in large part because of things like Bahram’s “going in disguise” having none of the charm of Sekander. At least Sekander sought knowledge, not just . . . . treasure, land, and chicks.

I do find interesting three specific aspects of the story.

One is the “folk tale” aspect of Bahram Gur’s collection of tales. He interacts a great deal with the common folk, whether dispersing coin, appointing headmen, or marrying their best looking women, and that suggests to me that for some reason he is seen as more accessible than the other kings. They pretty much only interact with the court, while Bahram is always out and about and drinking wine in local villages. Maybe this represents the reality of a king riding from place to place in his kingdom, or something specific in Bahram Gur’s tradition. Unlike Ardeshir or Shapur I, he doesn’t seem to have done anything particularly important or interesting, and yet he gets a huge long chapter–longer than either of theirs–and I would love to know if there are other story cycles that center around him. It seems there is always some guy who attracts the glamor for no discernible reason.

Another is the realism of the various wrestling for status and pride and power of the kings. I enjoyed the account of the campaign against the Chinese emperor: the deception about agreeing to send tribute but marching to make a surprise attack instead; the description of how hungry and thin the king and his soldiers got from their long march and how they had to take a day’s rest before they can attack the camp of the unsuspecting emperor.

Like you I was genuinely dismayed by the treatment of women. Even though there weren’t a lot of women in the first two thirds of the Shahnameh, they were almost without exception treated as intelligent women with agency, wealth, and the ability to make their own decisions (even if bad ones). In Bahram Gur’s take it’s all tits and ass, basically, and women whose reward in life is evidently to be able to gaze lovingly upon their husband-king. GAH. I am sad. I miss the badass ladies.

Who are the Luris? Enough negative stereotypes are present in their story that it makes me wonder.

Next week: The Story of Mazdak

Previously: Introduction, The First Kings, The Demon King Zahhak, Feraydun and His Three Sons, The Story of Iraj, The Vengeance of Manuchehr, Sam & The Simorgh, The Tale of Zal and Rudabeh, Rostam, the Son of Zal-Dastan, The Beginning of the War Between Iran and Turan, Rostam and His Horse Rakhsh, Rostam and Kay Qobad, Kay Kavus’s War Against the Demons of Manzanderan, The Seven Trials of Rostam, The King of Hamaveran and His Daughter Sudabeh, The Tale of Sohrab, The Legend of Seyavash Pt. 1, The Legend of Seyavash Pt. 2, The Legend of Seyavash Pt. 3, Forud the Son of Seyavash, The Akvan Div, Bizhan and Manizheh, The Occultation of Kay Khosrow, Rostam and Esfandyar Pt. 1, Rostam and Esfandyar Pt. 2, The Story of Darab and the Fuller, Sekander’s Conquest of Persia, The Reign of Sekander Pt. 1, The Reign of Sekander Pt. 2, The Death of Rostam, The Ashkanians, The Reign of Ardeshir & Shapur, The Reign of Shapur Zu’l Aktaf, The Reign of Yazdegerd the Unjust