Join Tessa Gratton and me as we read the Shahnameh by Abolqasem Ferdowsi. We’re using the Dick Davis translation (Penguin Classics).

Today’s portion: The Beginning of the War Between Iran and Turan

Synopsis: Manuchehr dies, leaving his crown to Nozar, who briefly loses farr which leaves an opening for Persia’s enemies to attack. During the long campaing, Nozar dies and Persia is left in danger of being conquered.

TG: I confess this might be my favorite section so far! I love war fiction and descriptions of massive military campaigns, especially when I’m invested in the players, and that is all these pages were! And because we’re so many weeks into this reading, I’m getting better at keeping track of who is who and who I care about, and why.

I’ve loved Qaren ever since he captured the castle of Alans for Manuchehr by tricking his way in and massacring so many of his enemies he turned the surface of the sea “black as tar.” I was seriously worried he was going to die early in this war, especially after his poor brother died (ah the wise Qobad! Alas!) and he went for revenge against the much younger Barman and Afrasyab. But he made it, for now at least. He got to be getting pretty old, but I continue to be delighted by his prowess and that Zal, too, relies on him to lead the armies of Persia.

(It was interesting that since the good guys were centered around Qaren and Qubod this time, the bad guys also had a brother duo, one a powerful warrior and the other known for his wisdom – though Aghriras never seemed so wise to me. They didn’t trust each other the way Qaren and Qubod did, which was, of course, their downfall as brothers.)

There was a lot of advice in this section, too, starting with Manuchehr’s advice for his heir Nozar, on the fleeting nature of rulership and life. That was the theme throughout both the advice and the narrative itself, as several warriors speechified on how they belong to death, that this earth is no more than a “cradle for death.” It smacks of destiny, though that’s not how it’s really presented. More like the inevitability of death, especially for warriors who work for death, as death-makers.

It was fascinating that Nozar could not only lose his farr (in the typical way), but regain it so easily. There’s not much narrative dedicated to him getting it back. We just learn the nobles explained to him how he lost is, and voila, he has it back.

Also fascinating: that Zal does not become the king of all Persia. He clearly has the farr (I think Simorgh saw it in him?) and when he hears good news of battle he celebrates by giving money to the poor and giving away his own coat to the messenger. If that’s not farr I don’t know what is! But instead they go searching through all Feraydun’s direct descendants and end up with an 80 year old, who does great, but only for those 5 years, and now there is no king!

I was worried about Mehrab for a moment, there: was he truly playing both sides, or was he only putting Shamasas off by pretending to be on his side until he could warn Zal?

I hope that after Rostam joins the battle, Qaren gets a great death in the next part of the war. If Zal is bent and old, Qaren must be incredibly white-haired, as they’d say.

KE: The constant discussions of death also intrigued me. Like you, I did not see this as a comment on destiny but rather more like the perspective in Ecclesiastes.

I too was worried about Mehrab because of his connection to Zahhak but so far he has proved steady and loyal, appropriately so for the grandfather of the future hero Rostam. But what a great reversal!

In fact this section more than any of the others had the narrative urgency of uncertainty. I really had no idea what was going to happen. I was prepared for anything and anyone to die, to be betrayed, to lose, or to win. The earlier sections have all had a sense of inevitability to them, in the sense that there wasn’t much sense of turning the pages to find out what happens next. You kind of know, or can guess, and it is more a matter of seeing how it plays out, or enjoying the descriptions, or being edified by speeches and erudite conversations between kings and councilors, and so on. So this was quite exciting as story, and actually the big plot feels as if it has scarcely begun. In a way I feel like everything that came up to now has been a prologue of a sorts leading up to the opening of this war.

I went back and re-read parts of the introduction to see if anything in these “legendary kings” section matches with known history but according to the intro the narrative doesn’t touch on any history that’s come down to us until a mention of the Achaemenid Dynasty right before Alexander is introduced. There is a suggestion that this king list could be from farther east of central Iran and thus part of a different regional tradition. This area of Central Asia has such a rich history and was such a center of scientific, literary, medical, and political civilization. It’s just fascinating. I wish I knew more about the history of Khorasan and Sogdiana and Bactria, this huge continental area that has always been a meeting point for cultures. I’ve read a bit but even so, much has been lost because of the successive waves of conquest and assimilation across the region.

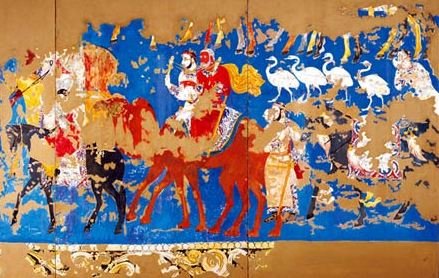

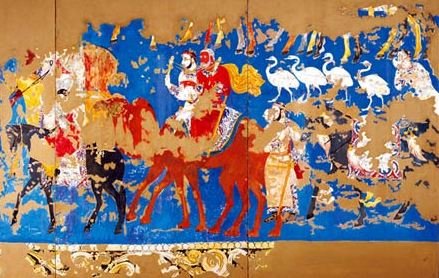

Here an image of a Sogdian era wall painting from Afrasiab.

I haven’t even talked about the brothers! Aghriras is such an interesting character because he’s one of the rare men who is not a warrior. With everything and everyone up in the air at the end of the section, I’m quite excited to see what comes next.

Next week (March 18) is a BYE WEEK. We return on March 25 with Rostam and His Horse Rakhsh

Previously: Introduction, The First Kings, The Demon King Zahhak, Feraydun and His Three Sons, The Story of Iraj, The Vengeance of Manuchehr, Sam & The Simorgh, The Tale of Zal and Rudabeh, Rostam, the Son of Zal-Dastan

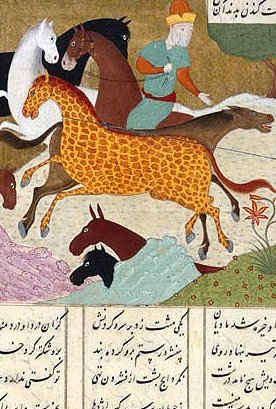

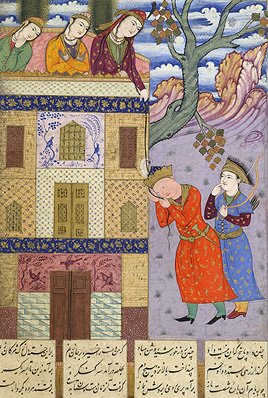

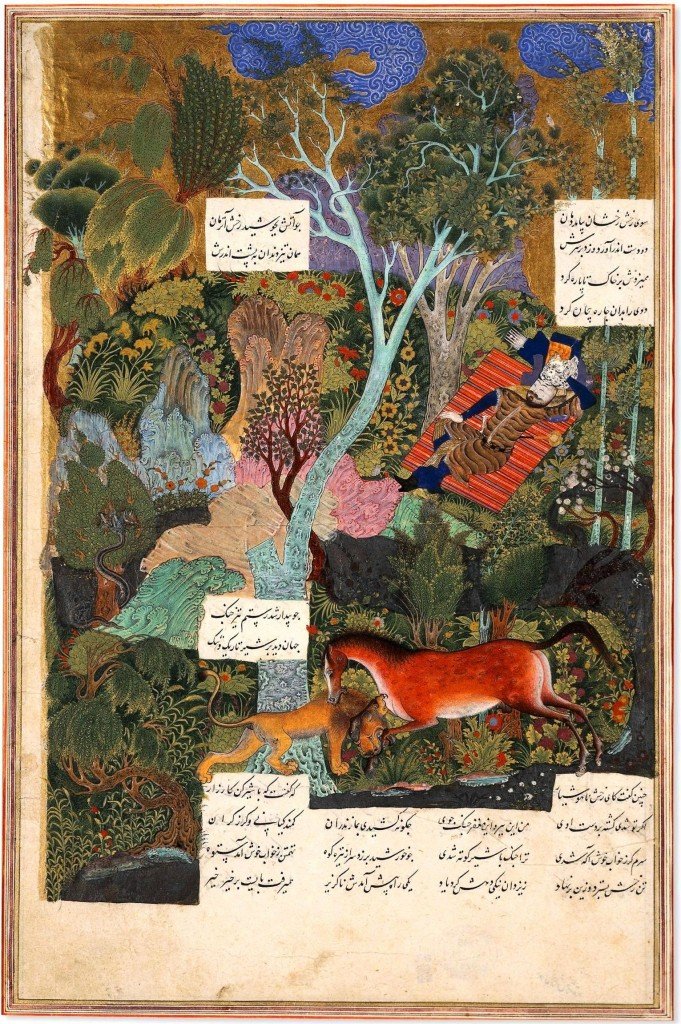

(Image from the British Museum)

(Image from the British Museum)