There are a lot of ways to write about strength.

As a writer I can get frustrated when a characteristic I mean to be understood as strong is interpreted by a reader as weak, even though I comprehend that every reader will bring a different interpretation to the table. Also, and more importantly, I get frustrated when I see myself as a writer falling into the trap of stereotyping “strength” and “weakness” in ways I don’t like and which I think are negative but which I revert to if I don’t stop and think past received assumptions about people and gender.

What do we mean when we say “a strong male character” or “a strong female character”?

What about “a strong character?” How does that come into play without it being tied to gender or sex?

And what do I mean by “we,” anyway? What about cultural and historical differences in how strength is defined?

What is strength?

There are so many ways to define strength in terms of the human personality and human characteristics and how it relates to what is valued in any given society at a particular moment in that society’s development or decline. What defines strength now may in twenty years or a thousand years be seen as a sign of potential weakness, while something I define as weak may be seen as strong elsewhere.

Actual physical feats of strength range from a simple measure like weight-lifting to a more complex measure like physical endurance. As a woman I have been told more times than I care to count that men will always rule human civilization because they are physically stronger by what I call the weight-lifting measure, an opinion that oddly leaves out humanity’s crucially advantageous traits of dexterity, adaptability, creativity, intelligence, and persistence. And what about endurance? In some ways, endurance is the greatest test of strength.

Is strength a way to tear things down or to build things up? In the Bible, Samson famously does both, although it is important that while his strength is commonly defined as physical in fact, as a Nazirite, it is his spiritual strength that has nurtured his physical strength.

Sometimes it seems like portrayals of strength in the (heavily USA-based) media I see around me are getting choked through narrowing definitions. I say that in part because I think mainstream US media is going through one of its cyclical restricting modes, while meanwhile in the global gestalt a new creative energy and vision is expanding with increasing vigor.

Part of that is because views about strength, like views about anything, go through fashions: the strong silent cowboy becomes the blustering self absorbed Rambo; the man too honest and righteous to break the law becomes the man who breaks the law to make things right; the calm moderate in-control man becomes the angry passionate man while meanwhile in many societies being unable to contain or control anger is seen as a flaw rather than as a sign of strength.

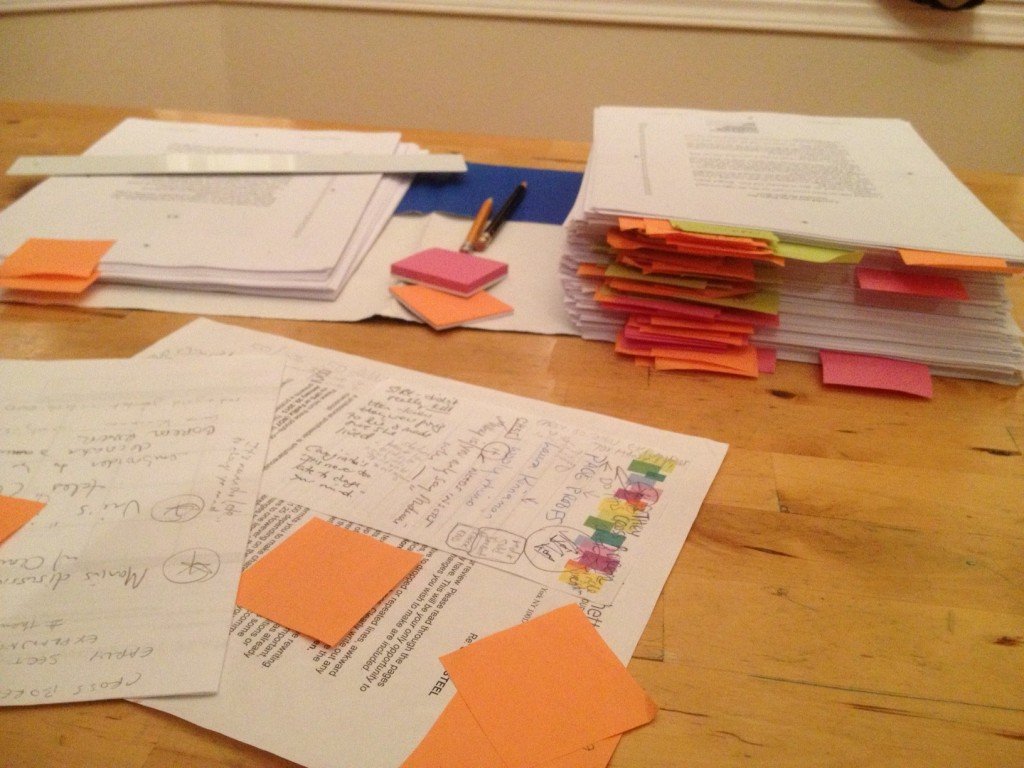

During the writing of Cold Steel I had a series of email exchanges with Michelle Sagara about definitions of and assumptions about masculinity in our culture.

I was concerned that a particular character might not be seen by some readers as a “strong male character” because he does not display several of what are typically (although not exclusively) seen in today’s media/fiction as “strong male” characteristics. This isn’t an exclusive or finite list, but two of the characteristics I identify as seeming to me to be stereotypical today as approved markers of masculinity are the “man as soldier” (or warrior) which is related to but not exactly the same as the man who uses violence (and kills) to righteously solve problems. I still also see elements of a type I call “the masterful man,” the man who won’t take no for an answer, who knows what he wants perhaps better than you do, who pushes until he gets what he wants. This is a form of what is often called “the alpha male” but by no means the only example of the type. All three of these types seem to me important in an imperial context: That is, an empire tells stories about itself to justify the empire, and some of those stories naturally will include valorizing war and soldiering, violence, knowing better than others, and the idea of exceptionalism, that the empire is destined to rule and/or somehow favored by god, chance, Fate, or destiny.

Leave aside for the moment the larger and related question of what exactly we mean when we say male, female, man, woman, and so on ( I’m no gender essentialist regardless). And for the moment I’m speaking about my experience primarily but not exclusively with American English-language media and fiction.

If strength is defined in limited ways, then human character is not only limited but harmed by being forced to adhere to increasingly smaller sets of perceived value. When certain characteristics got locked in as strong and others ignored, or derided as weak, it creates a restrictive view of humanity.

Crucially, for writers, narrow definitions of what constitutes a strong man or a strong woman can affect how people read and view those characters. Some readers will reject a character as strong because that character does not adhere to stereotypes of “strong.”

For instance strength can be expressed through patience, and patience is a characteristic that both men and women have. But if patience is not seen as a masculine characteristic, then a male character in a fictional story characterized as patient may or may not be seen as a strong man. For example, the film Witness contrasts Harrison Ford’s world weary and violent cop with Alexander Gudonov’s non-violent, patient, quiet Amish farmer (it finds both men ultimately positive as role models but I note that the story revolves around Ford’s cop).

If male characters can’t be seen as strong except when martial or angry or violent or masterful in the sense of being forceful, then think how harmful that becomes to our understanding of what it means to be a man and the cultural creation of role models for boys to grow into. Think of how harmful it is for women.

And what about women? What is a strong woman? One who kicks ass and can fight “as well as a man”?

As many have pointed out before me, if women only get to be strong insofar as they look and behave like men, then that does not uplift women.

If characteristics long defined as “feminine” are automatically derided as “weak” or undervalued and dismissed as “girly,” then those attitudes affect all children as they grow into adulthood just as restrictive attitudes about boys affect all children likewise.

I love stories and characters that celebrate diverse ways to be strong.

In Grace Lin’s Where the Mountains Meet the Moon, Minli is stubborn and determined. And she listens.

Oree, in N. K. Jemisin’s The Broken Kingdoms, has a clear and powerful sense of herself that makes her strong.

In Michelle Sagara’s Silence, the main character Emma is caring and loyal to her friends and to others. I tend to find compassion a sign of strength, and it appeals greatly to me in characters.

In Cold Fire, I deliberately had Andevai court Cat not with manly arrogant alpha-ness but with patience and food.

While Nevyn in Katharine Kerr’s Deverry sequence does fit the acceptable mode of the “mysterious and wise old man with magical powers” character, he himself is strong because he uses his mind, is often kind and patient, and because he fulfills a very long burden of service to make up for a wrong he caused. That’s strength.

The sisters in Aliette de Bodard’s story “Immersion” are strong by being smart, observant, thoughtful, and (again) determined. Their radicalism is quiet, necessary, in some ways tentative, and within its small orbit it is effective.

Strong female characters in Danish tv shows like Forbrydelsen, Matador, and The Eagle work well for me because they are portrayed as competent, intelligent, no-nonsense, pragmatic, efficient, compassionate, caring, and steadfast.

Of course every reader brings their own view of strength to the table.

What portrayals of strength (from any fiction) have you liked that did not fit with classically stereotypical kickass or martial or alpha-manly definitions of strength? Do you think that SFF and YA, for example, are pushing the boundaries of what is seen as strong or are more likely to fall back into more standard modes of “strength expression”? Are all characters given equal chance to be seen as strong, or are some given more limited roles than others?

I have no definitive answers. I’m just asking questions here.