The Shahnameh 2016 Readalong had its genesis in a fortuitous exchange on Twitter. Tessa Gratton and I decided to divide the book up as one would in a college course and read the entire epic by Abdolqasem Ferdowsi across the year, blogging our reactions along the way. And so here we here, having read the entire Dick Davis translation although, because Davis abridged elements, not the entire epic. Herewith our thoughts, which end up focusing both on reading and on how a process of idea and writing development work.

Tessa: I bought my copy of the Shahnameh a little over two years ago. I’d just finished the final book in my United States of Asgard series, and planned to write some stand alone novels over the next few years, while reading, learning, investigating the background for whatever my new (next) (eventual) giant fantasy series would be. I only had the core idea, and because I’ve been writing for over a decade I know my imagination needs a lot of time and layers to start the soup that will become a vibrant, complicated secondary world culture big enough for a series. So even though I wasn’t planning to write that series yet (I’m still today probably two years away from writing the thing), I needed to begin the process of feeding the specific location in my imagination that would chew on the idea.

Most of my research materials for this project are nonfiction. Histories of the culture and locations, from ancient to modern, written by people from within and without the culture itself, with a focus on architecture and clothing/tools. Some biographies. And a very small number of fiction and mythology sources—as close to primary sources as I can find. I bought Shahnameh knowing only that it’s a chronicle of kings, rather like the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle meets Beowulf, but more important and influential to Persian culture than either of those aforementioned works. I also knew it was long. Very long.

When Kate mentioned on Twitter that she was thinking of making a project out of reading it, my copy had been sitting about 10 inches away from my computer for over a year, and I knew I had to jump on the opportunity if I wanted the best chance of reading every word.

I’m so glad we made this project. Not only because it’s given me an opportunity to work with an author I’ve admired for years, but breaking the Shahnameh down in weekly installments and writing up my thoughts forced me to focus on engaging carefully with the text as a reader as well as a writer, instead of trying to blaze through on my own energy, gathering only what I knew I needed instead of allowing time and space to discover what I did not know.

Discovering what I don’t know about a culture and place and time is what matters most to me when I want to be true to the rhythm and sensations of a world, not just the surface.

With regards to my writing, reading the Shahnameh has been an invaluable research experience because of how fiction breathes life into ancient peoples, especially fiction created so long ago—the Shahnameh brings me halfway to Ancient Persia in ways no recently written history or novel can. It transports me into the mindset of people fifteen hundred years ago, to what they thought was important to highlight about the Persian kings from a thousand years before that. The layers of prioritizing and purpose matter so much when analyzing and embracing a work like this, not only to my understanding of the story, but my understanding of how I myself will rework and translate the ideas and culture into what I eventually write. This version we read has a translator (Dick Davis) who chose what words/ideas/sections to highlight (and which to erase), and the original poet Ferdowsi who himself chose what kings/ideas/episodes to highlight for his very specific audience. Then we have the stories themselves, and how and why they survived in order to reach Ferdowsi’s imagination in the first place. Beyond even that, there’s the layer of my POV, my situation as a Western woman long interested in the conflicts in the Middle East for both personal and political reasons. In addition to how it directly affects my writing, the Shahnameh has helped me think through current war and politics, reshaping my understanding. Every work of fiction has layers like this, layers of perspective, expectation, prejudice, and I need to remember that at every stage of my writing process.

All this was constantly on my mind as I read, but what will stick with me longest, I suspect, is the very gripping sensation of inexorable despair that I felt several times while immersed in the stories. I’m thinking most specifically of Seyavash, of course, and secondarily of Rostam’s doomed son, of Zal surviving all his children and grand children until he goes off to a mountain alone, in some ways the first and the last of his wise-wizard archetype in the Shahnameh. It’s amazing that Seyavash’s story could resonate so strongly for so many hundreds of years, beginning in this conflict between the Persians and Arabs thousands of years ago, with what they revered and feared, and eventually finding a home in my heart, too. That kind of emotional resonance is what literature is for.

Thank you, everyone who tagged along, keeping us honest, and thank you especially to Kate for making it happen.

Kate: After Tessa sent me her comments I felt she had basically covered what I would say, especially with respect to world building and research: I start by figuring out what I don’t know. There’s a lot I don’t know. This is why the structure and approach toward research feels important to me as a writer. The more I assume I know, the less I can actually learn.

For decades I’ve had an intense interest in the history and mythology of the Silk Road, I think in part because an aspect of me loves the resonance of long distance travel as a theme or anchor, if you will, for narrative. The ways that cultures rise and fade across centuries, the ways cultures connect and conflict, absorb and reject, transform or remain static: As a writer this is thematic content that never gets old for me. A million million stories rise out of the endless back and forth of cultural contact in all its best and worst aspects, and everything in between. Weave that within a story of adventure or empire or a journey into unknown spaces and I’m in writer and reader hog heaven.

So my early interest in the Silk Road led me to an interest in the history of Iran, and my interest in the Hellenistic Period led me to its intersections with ancient Persia. In late 2014 I read Frederick Starr’s book Lost Enlightenment: Central Asia’s Golden Age. It’s a non fiction work about the rich scientific and literary landscape of Central Asia during what was also the early Middle Ages of Europe and how much of that Central Asian scientific work was brought into a less advanced European system. It’s specifically written for Western readers; that’s fine because it’s a good introduction that contextualizes the material for a readership assumed to be looking in from the outside. A work like this can be a starting point but should not, to my mind, be an end point. Although I was aware of the Shahnameh, of course, Starr’s book did make me start thinking more seriously about reading Ferdowsi’s epic, but it’s a long work and therefore rather daunting.

That’s why it worked out so amazingly well when Tessa said she’d be interested in reading it along with me. Positioning it as a year long project split into discrete and manageable sections made it . . . manageable.

Reading the Shahnameh gave me a glimpse from the inside (via a translation) into the incredibly rich heritage of one of the world’s most profound and complex civilizations, that of Persia. Now when I see references to characters or events I have a connection, however frail, that links me to that cultural heritage. We all live within shared heritages, and sometimes we live within overlapping ones, so that my shared cultural heritage as a person born and raised in the USA overlaps with my shared knowledge of 20th century rural Willamette Valley Oregon, with the Danish American experience, with being Jewish in America, with having parents who lived through World War 2, and with the larger cultural “regions” each of these attach to. What I’ve listed above is not the sum of my experience, just some examples, but the point is that having read the Shahnameh I now have a few touch points that connect me to a culture and history I was taught so little about and that mostly in simplistic terms.

One of the things education and experience can do is expand our touch points, those places in which we recognize and acknowledge and at times share the experiences of people who may be separated from us along other vectors of experience. So for example, Ferdowsi and I are separated by a gulf of time and culture (I don’t speak Persian so I can’t read his work in the original), and yet we are both writers so when he complains about not getting paid for his work I feel a sense of solidarity. How dare we not get paid for the work we do! *shakes tiny fist at world*

The lives and destinies of his characters now offer me a window through which I can communicate with people who also know these stories. We can enjoy the story’s fascinating take on Alexander the Great as trickster and seeker-of-wisdom, cheer on confident Rudabeh as she invites the handsome Zal to her chambers, and weep together over Seyavash’s tragic fate. It means something important when these connections are made and bridges are built. As human beings we talk to each other so much through shared understanding of stories.

Tessa and I also often remarked on what Davis left out of his translation (she covers this discussion, above, in much the same terms I would), and that too is a fruitful space to think about how people understand the world and how the world gets “translated” (or mis-translated) for different people in different spaces and places. We have to keep pushing at the closed gates and narrowly-framed windows that limit our access of vision.

What an amazing epic story the Shahnameh is, both as the national epic of Persia and as a vital vehicle in sustaining the Persian language. It is also fascinating in terms of its own history and tradition, not just in terms of Ferdowsi’s life and work but because the existence of a “Book of Kings” in the Persian cultural zone goes all the way back at the very least into the Achaemenid period.

Strangely enough I have a project in the early stages of development and writing that is partly inspired by a period of ancient history in which the Achaemenid Empire was a major player. But that’s another story built on the edifice of Story that surrounds us and creates us, because humans are pattern makers and story tellers. It’s hardwired into us to build our lives as narratives.

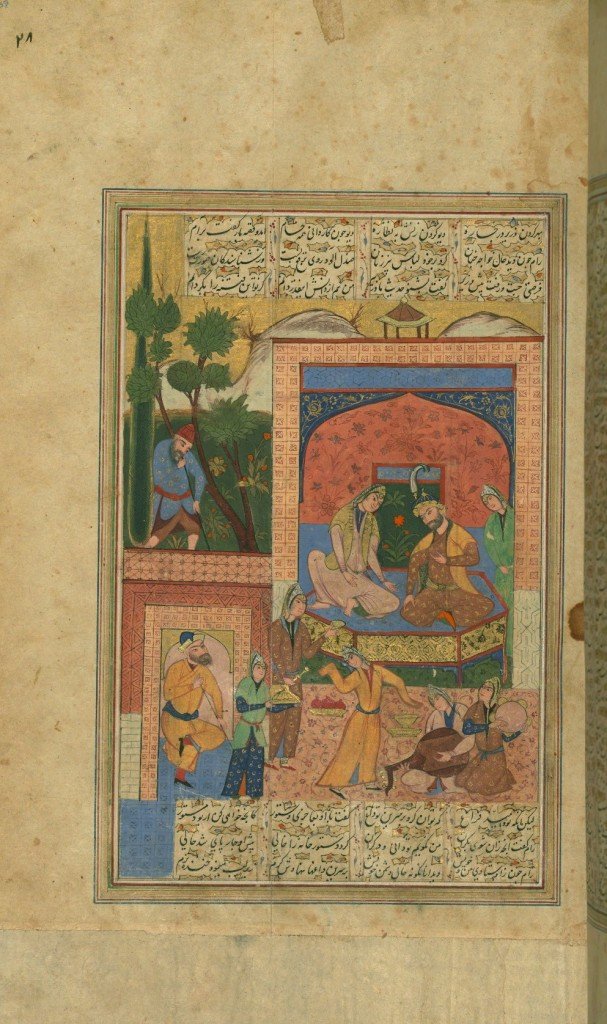

So if you haven’t read the Shahnameh, I recommend it. Go forth and read. Or at the very least search out the gorgeous artwork commissioned over the centuries to illustrate the many characters and iconic events.

This is still perhaps my favorite illustration that I’ve shared in this readalong for its gorgeous composition, colors, detail, and beautifully delineated human figures:

Thanks to Tessa for the shared journey because I could not have done it without her, to Paul and Rachel our most consistent comrades on the march, and to all who read along for part or all or some of the way.

And yes, I’m doing another readalong in 2017, this time of the Chinese classic The Water Margin (Outlaws of the Marsh).

Happy New Year!

Missed any of the Shahnameh Readalongs? Here are the links to each of the 41 entries:

Previously: Introduction, The First Kings, The Demon King Zahhak, Feraydun and His Three Sons, The Story of Iraj, The Vengeance of Manuchehr, Sam & The Simorgh, The Tale of Zal and Rudabeh, Rostam, the Son of Zal-Dastan, The Beginning of the War Between Iran and Turan, Rostam and His Horse Rakhsh, Rostam and Kay Qobad, Kay Kavus’s War Against the Demons of Manzanderan, The Seven Trials of Rostam, The King of Hamaveran and His Daughter Sudabeh, The Tale of Sohrab, The Legend of Seyavash Pt. 1, The Legend of Seyavash Pt. 2, The Legend of Seyavash Pt. 3, Forud the Son of Seyavash, The Akvan Div, Bizhan and Manizheh, The Occultation of Kay Khosrow, Rostam and Esfandyar Pt. 1, Rostam and Esfandyar Pt. 2, The Story of Darab and the Fuller, Sekander’s Conquest of Persia, The Reign of Sekander Pt. 1, The Reign of Sekander Pt. 2, The Death of Rostam, The Ashkanians, The Reign of Ardeshir & Shapur, The Reign of Shapur Zu’l Aktaf, The Reign of Yazdegerd the Unjust, The Reign of Bahram Gur, The Story of Mazdak, The Reign of Kesra Nushin-Ravan, The Reign of Hormozd, The Reign of Khosrow Parviz, Khosrow and Shirin, The Reign of Yazdegerd