Join Tessa Gratton and me as we read the Shahnameh by Abolqasem Ferdowsi. We’re using the Dick Davis translation (Penguin Classics).

This week’s portion: The Legend of Seyavash (third of three parts, this part starting on page 259 and going until the end of the section)

Synopsis: Garsivas turns Afrasyab against Seyavash, who is murdered. His son by Farigis is born.

TG: This was terrible. I’m so upset I can’t make paragraphs.

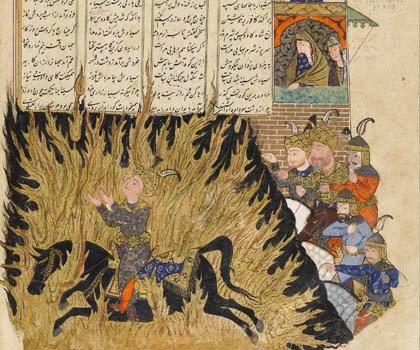

1) Seyavash doesn’t even get to die in battle! Instead he’s captured and his throat is cut like he’s an animal. D: D: D:

2) Garsivas just… gets away with it? WTF I am very angry about that. I skimmed ahead and I don’t see any retribution coming for him. VERY distressing. He just turned everybody against each other, for jealousy and bitterness, and he doesn’t even get to find out Seyavash is his grandkid, and tear out his hair???

3) I take back every nice thing I’ve ever said about Afrasyab. He’s way too easily manipulated.

4) I’m less sure about the timing of all this… since right after this Kay Khosrow becomes king, either we were wrong about the timing of the incident with Sohrab, or it happens while Khosrow is growing up in secret with the shepherds?

5) I loved it when Farigis calls Seyavash “my lion lord.”

6) It was interesting that Seyavash could give such a specific prophecy to Farigis about her future and his son, down to how they would escape Turan, but all his own personal prophecies were so much more generic. I wonder if there are rules to that (I’m constantly in search of magical rules, and the Shahnameh doesn’t have many).

7) I love that in Seyavash’s absence Seyavashgerd became a wilderness of thorns.

8) Someday I might start a novel “On a dark, moonless night, when birds and beasts were sleeping, the lord Piran saw in a dream a candle lit from the sun. Seyavash stood by the candle, a sword in his hand, crying out in a loud voice, ‘This is no time for rest; rise from sleep, learn how the world moves onward; a new day dawns and new customs come; tonight is the birth of Kay Khosrow.'”

It is just so inspiring and beautiful– or possibly I just already miss Seyavash so much I was thrilled for another appearance.

KE: I’m in total agreement. The death of Seyavash is by miles the most dispiriting event in the Shahnameh so far. Obviously the degrading manner of his death is on purpose, including the one person who speaks out against it and isn’t listened to. It’s not just degrading to Seyavash; it dishonors those who kill him like this, and it is clear they are considered beyond the pale (at least by the author).

I also skimmed ahead to see if Garsivaz gets his comeuppance and yet, despite everything, he apparently does not (maybe he is a footnote in the coming fall of Afrasyab). Shades of Iago, though: People resist his nasty insinuations at first and then fall for them, perhaps out of his sheer persistence. This is one of the most depressing forms of story: the envious courtier who destroys the people he is envious of, sowing destruction and bitterness wherever he goes. I had hoped Seyavash would see through him as he saw through Sudabeh, but it does seem a combination of getting worn down (and not suspecting G’s duplicity) and then his own prophetic powers.

It was also interesting to see the contrast between his friendship with Piran and that with Garsivaz. Seyavash treats the two men more or less the same but one always feels that Piran is the more genuine.

I love Faragis in this. Her obvious love for him (I also adored “my lion lord”) and how she pleads for his life. As with most of the women we have seen so far, she is well educated, well spoken, intelligent, and unafraid to speak her mind (at least at dramatic points in the story). She does not cower.

Also I would have loved to know more about Piran’s wife, briefly mentioned BY NAME (we still don’t know the name of Seyavash’s mother), Golshahr. One of the interesting things for me about the Shahnameh is, as I’ve said before, the sense within the text that this merely scratches the surface of a much larger cycle of tales. How fortunate we are that Ferdowsi lived and wrote when he did because if he had not, much of this would have been lost as the great Persian culture was partially subsumed by Islam/Arab culture (although obviously Persia has always retained its own identity as one of the great, noble civilizations of the world).

After finishing (and crying) I re-read the part of the introduction where the translator talks about what parts he chose to leave out. I couldn’t help but notice the italicized synopsis at the end in which it is mentioned in a sentence that Kavus had Sudabeh executed! The events referred to in that synopsis seemed so important to me, but perhaps they weren’t as interesting to read? I don’t know. This is one of several fundamental issues with translation: it is always a form of gatekeeping in which the translator (or abridger) makes choices and we are then left reading a version that may seem to us as the complete one when in fact it is incompletely. I don’t fault Davis, who has done a wonderful job. Just noting how often people and events are left out as “insignificant” or “unimportant” when that is always a judgment call by a subjective scholar or translator.

As for the issue of chronology, now I am wondering if there is any scholarship on that.

And, yes, please do someday start a story with that paragraph.

*weeps*

#

Next week: Forud, The Son of Seyavash

Previously: Introduction, The First Kings, The Demon King Zahhak, Feraydun and His Three Sons, The Story of Iraj, The Vengeance of Manuchehr, Sam & The Simorgh, The Tale of Zal and Rudabeh, Rostam, the Son of Zal-Dastan, The Beginning of the War Between Iran and Turan, Rostam and His Horse Rakhsh, Rostam and Kay Qobad, Kay Kavus’s War Against the Demons of Manzanderan, The Seven Trials of Rostam, The King of Hamaveran and His Daughter Sudabeh, The Tale of Sohrab, The Legend of Seyavash Pt. 1, The Legend of Seyavash Pt. 2