Join Tessa Gratton and me as we read the Shahnameh by Abolqasem Ferdowsi. We’re using the Dick Davis translation (Penguin Classics).

If you haven’t already don’t forget to check out this AMAZING post by Rachel W in which she works out the complicated genealogy of our main and secondary characters.

This week’s portion: The Occultation of Kay Khosrow

Synopsis: “The king, fearing he will fall to temptation like his predecessor,s prays to God, who tells him to give away his possessions and disappear into the mountains. Nobody is happy about it.”

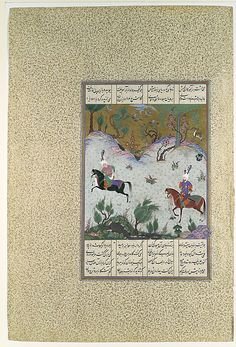

The angel Sorush watches or guides the king ascending into the heavens as lords wait around a fire, below. The background is white, depicting snow.

TG: Also known as “that time five Persian warriors DIED IN THE SNOW.”

Damnit, Bizhan, you were supposed to live happily ever after, not DIE IN THE SNOW.

So mostly I liked this chapter a lot, because it was so different, but the intrigue depended on the history and patterns established in all the hundreds of pages before it. In order to understand both Zal’s side and Khosrow’s side, we have to have been with these previous warriors and kings so that we can see exactly what Khosrow is afraid of AND understand why Zal thinks everything is wrong and terrible.

It seems very smart of Khosrow to recognize that it’s his nature to be tempted to the Dark Side like basically every single one of his ancestors on both sides of his family have been. He doesn’t have a threat to face down, so his idle mind turns toward temptation. The surprising thing is that he’s learned from Kavus’s incredible mistakes (oh that flying machine, I love that it’s the thing Zal is most pissed about, too, because WHAT a doozy), and does the right thing: he asks God for guidance.

There was a lot of wisdom thrown around in this chapter, especially about how to act justly and how to be a good king, as well as the kind of actions that the Persians deem worthy of the highest rewards. And Khosrow spent a good amount of time comforting his wives and talking about who was awaiting them in death. I want to know more about this Mah Afarid though.

We get a bit of a flawed Zal, especially with regards to a vicious sort of classism in his immediate rejection of Lohrasp, which was interesting, and I’m delighted the two came to an accord. The visual of Zal smearing dirt on his mouth to blacken his lips and cancel his sin is maybe my favorite moment of the entire book so far.

This Goshtasp we’re skipping over sounds like a RIOT so that’s too bad. And ZOROASTER I’ve been waiting for him to show up, and am pretty disappointed it won’t be on page.

Cannot believe all those dudes died in the snow.

Seated on a cloud like vessel and attended by angels, the king ascends into the heavens. Below, men gather around a fire, arms raised toward the sky.

KE: I found this story quite gripping. The consternation and befuddlement of the courtiers in regard to Khosrow’s strange behavior worked well, especially as contrasted to the endless partying in the garden scenes from before. The debate between Khosrow and Zal, and the way Zal is able to not only see that he has misjudged the situation but makes a clear and public declaration of it, was for me quite suspenseful, however odd that may seem when we are so accustomed to page-turning meaning there is lots of physical action and violence.

I’m traveling so can’t find the quote but I loved the comparison with the shining moon and how it can be darkened.

Like you, I did feel Khosrow was right to be concerned about losing his farr given the history of Jamshid and Kavus, just to name two. Yet for all that what most struck me is this: He was completely caught up in analyzing his own behavior, fixated on his own legacy, really concerned only with himself. No where are his connections to others signaled as primary. He never knew his father although much of his legitimacy and fame comes about because he revenges Seyavash’s death. Once his mother delivers him to Persia she vanishes from the story (as far as we know from this translation). His wives (if they are wives rather than concubines) don’t have names or context beyond his palace. Given that he has to name an unknown as his successor, he either has no worthy sons or NO SONS AT ALL.

Contrast this with the endless discussion by other princes and lords about their brothers, sons, and grandsons, their pride in and love for them; even occasionally their love and respect for daughters and wives (and sometimes mothers). For me, it felt as if Khosrow was a man with no place in the world except as peerless ruler. He evidently has no descendants, nothing to hold to as a legacy except the idea that he must have a spotless reputation. It’s not that having a child is the only path to meaning in life. It isn’t. But contextually in a story about legacies and generations, and men who to a great degree measure their success in life by knowing they have a worthy successor of their own lineage, Khosrow’s situation stood out for me.

Like you I was again frustrated by wondering what we are missing in the synopsized portion. I don’t know why these cuts are showing up now except that, as per the introduction, the translator felt there was repetition of theme and action. But I am sorry to have missed Goshtasp.

And while I basically know nothing about the Persian language, this shift of names interests me: Lohrasp, Goshtasp, Arjasp. Don’t these sound like regional differences or even a different (perhaps related) language? I don’t know, maybe not, but I wonder if it signals a shift in dynasty linguistically as well as politically, and I also wondered how it related to the arrival of Zoroaster.

In fact the mention of Zoroaster got me all excited but, alas, we skip over it. It does mean the story is now venturing into history known to us (although I grant you not much is actually known about the historical Zoroaster); I don’t know what historical sources and legends Ferdowsi had access to a thousand years ago that were obliterated or lost due to the Islamic conquest and/or the passage of time.

#

Next week: Rostam and Esfandyar (first of two parts, I don’t have page numbers on hand because I’m writing this while traveling but read about 26 pages). Somehow I suspect this will end tragically because when Rostam gets involved that tends to be the outcome.

Previously: Introduction, The First Kings, The Demon King Zahhak, Feraydun and His Three Sons, The Story of Iraj, The Vengeance of Manuchehr, Sam & The Simorgh, The Tale of Zal and Rudabeh, Rostam, the Son of Zal-Dastan, The Beginning of the War Between Iran and Turan, Rostam and His Horse Rakhsh, Rostam and Kay Qobad, Kay Kavus’s War Against the Demons of Manzanderan, The Seven Trials of Rostam, The King of Hamaveran and His Daughter Sudabeh, The Tale of Sohrab, The Legend of Seyavash Pt. 1, The Legend of Seyavash Pt. 2, The Legend of Seyavash Pt. 3, Forud the Son of Seyavash, The Akvan Div, Bizhan and Manizheh