Join Tessa Gratton and me as we read the Shahnameh by Abolqasem Ferdowsi. We’re using the Dick Davis translation (Penguin Classics).

This week: The Reign of Shapur Zu’l Aktaf

Synopsis: “Shapur, Lord of the Shoulders, battles against Rome after being sewn into the skin of an ass, and rules for fifty years.”

TG: It’s strange to think of an episode that includes a king being sewn into the skin of a donkey as generally just more of the same, but that’s what it is. I enjoyed it, and would never call it boring, but these sections are beginning to feel familiar. They follow the same frame, of coming to and leaving kingship, and then the pieces are filled in with recognizable incidents, and while that can get repetitive, it really lets the details shine. Not only details like the donkey skin, but also details about the women and secondary characters, who they’re related to, and asides (like how Shapur got his epithet).

Overall there are two things I really noticed:

– I’ve gotten used to the section headings, and for the most part they only gently suggest what’s about to happen. They’re “so and so fight so and so” or “so and so is killed” or “so and so sees our hero and falls in love.” But when I got to “Shapur Travels to Rome and the Emperor of Rome Has Him Sewn in an Ass’s Skin” I had to read it twice.

And then I sat there, mouth open, and thought how I couldn’t WAIT to find out how this was going to come about, and why. It was a great reminder that sometimes a spoiler really pushes me eagerly on.

– I wonder how many descriptors of beauty are gendered. I expect most, or all, to be, but in the Shahnameh very few seem to be. I think “face like a moon” is generally used for women, but like a cypress tree, musk smelling, rosy cheeks, all these things are said of men, too. Shapur’s description in particular struck me as very “feminine” which of course made me sit back and think about my OWN assumptions and use of adjectives and metaphors and how I gender them (and play to and on reader expectations).

It’s nice in the final quarter of this epic book to feel familiar enough with the context and rhythms of it to really dig into some of these things for myself.

#

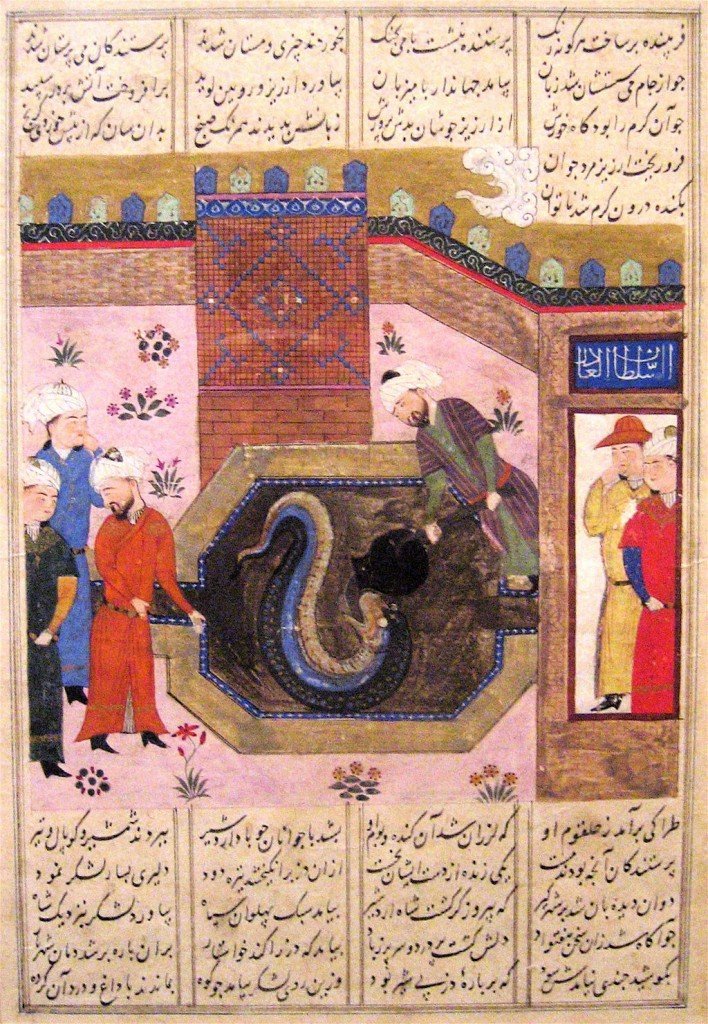

ILLUSTRATION NOTE: For the first time ever, I have not been able to find a lovely Persian miniature painting from the section we are reading this week, so have a painting of Shapur I using Emperor Valerian as a footstool to mount his horse.

#

KE: I too felt the drum of familiarity in this section–a king in disguise as a merchant, battles and more battles, the countryside devastated, a man saved by a clever and beautiful young woman–with the notable exception of the ass’s skin. What an amazing detail!

At least the young serving girl who saves the hapless king is given a name by him. Did she have a name before or was she literally nameless? Perhaps this is a special honor name? I don’t know the customs but was pleased to see her honored because so few women get named in the saga that it’s nice to see one get her due.

The episode of the Ass’s Skin is definitely one of my small highlights of the entire book just for how strange and somewhat grotesque it is to imagine.

And yes, I do also feel we are consistently seeing a somewhat different beauty aesthetic than the one we are accustomed to. Although youthful beauty is a theme cross culturally worldwide, I suspect.

The revolt of the Nasibins also interested me; they don’t want to be ruled by a Zoroastrian king, and pay the price for it. Also note that very odd aside in which Shapur criticizes Christianity by saying, “It’s ridiculous to respect a religion whose prophet was killed by the Jews.” I don’t know any way to read this except as anti-Semitic, but maybe there is another interpretation. Neither do I have any idea of whether the Sassanians were particularly anti-Semitic, and if not, where this comes from.

Speaking of religion, I was struck by how the section concludes with a curious and unexpected mention of Mani, the founder and prophet of Manichaeism, at the end of which Mani meets a violent death (as he did in real life). Since Zoroastrianism *was* the state religion of the Sassanian dynasty, as far as I know, it makes sense that it plays a larger role in the story now. One of the things bad and simplistic history teaches is that the Muslim conquerers of Persia basically made everyone convert at the point of their swords immediately but in truth that didn’t happen at all. Zoroastrianism hung on for centuries (and there is still a remnant community), and often people converted either out of piety or because it benefited them in some way. I don’t think the Book of Kings will get into that, though, since we’ve already been told that Islam is never mentioned in the story although Ferdowsi wrote after the Islamic conquests.

So I peeked ahead to the reign of Yazdegerd the Unjust and I can just say that Yazdegerd’s son Bahram looks to be the nastiest toward women yet. Imagine my emoji face.

#

Next week: The Reign of Yazdegerd the Unjust

Previously: Introduction, The First Kings, The Demon King Zahhak, Feraydun and His Three Sons, The Story of Iraj, The Vengeance of Manuchehr, Sam & The Simorgh, The Tale of Zal and Rudabeh, Rostam, the Son of Zal-Dastan, The Beginning of the War Between Iran and Turan, Rostam and His Horse Rakhsh, Rostam and Kay Qobad, Kay Kavus’s War Against the Demons of Manzanderan, The Seven Trials of Rostam, The King of Hamaveran and His Daughter Sudabeh, The Tale of Sohrab, The Legend of Seyavash Pt. 1, The Legend of Seyavash Pt. 2, The Legend of Seyavash Pt. 3, Forud the Son of Seyavash, The Akvan Div, Bizhan and Manizheh, The Occultation of Kay Khosrow, Rostam and Esfandyar Pt. 1, Rostam and Esfandyar Pt. 2, The Story of Darab and the Fuller, Sekander’s Conquest of Persia, The Reign of Sekander Pt. 1, The Reign of Sekander Pt. 2, The Death of Rostam, The Ashkanians, The Reign of Ardeshir & Shapur