Join Tessa Gratton and me as we read the Shahnameh by Abolqasem Ferdowsi. We’re using the Dick Davis translation (Penguin Classics).

If you haven’t already don’t forget to check out this AMAZING post by Rachel W in which she works out the complicated genealogy of our main and secondary characters.

This week’s portion: Bizhan and Manizheh

Synopsis: Another contained episode in which Rostam saves Bizhan from the clutches of Afrasyab with undercover work and actually! trusting! a! woman!

TG: I didn’t dislike Rostam so much in this one, since he showed a lot of interesting initiative and thoughtfulness regarding how best to get Bizhan safe, instead of just crashing wildly in because he CAN. I loved that he and the other warriors went in as merchants, basically spying on the Turks at first to discover the best way to get Bizhan out.

And of course that best way was to let Manizheh help.

OH MANIZHEH. I love her. She is rich and takes what she wants damn the consequences (she gets this from her dad, no doubt), including drugging Bizhan and kidnapping him! She’s bold and also loyal once she’s given her heart. But the best thing about her is how she stands up to men who are treating her like she’s not worthy of them: Rostam and Bizhan. They both act like she can’t be trusted, or are mean to her, and she stands up and basically cusses them out for being unfair fools. And it works! They change their behavior. It’s clear the narrative is on her side about Rostam and Bihan’s treatment of her.

She gets her reward, too, for sticking with Bizhan and helping him escape.

I am livid Afrasyab’s execution is a footnote. And Piran’s stoic, noble death, too. What the hell, Davis? Given how painful reading Seyavash’s death was, I expected some emotional payback getting at least a little bit vengeance in Afrasyab’s death. But no! It’s a footnote and not only that, but Garsivaz is still being a terrible counselor and still alive.

I’m curious about what this means about the purpose of the over-arching narrative. We’re supposed to focus on the suffering of our heroes, and be less invested in relishing vengeance? Are we, like Bizhan, supposed to “drive all thoughts of hatred” from our hearts and forgive the bad guys? At least to the point where the story isn’t ruined by not being allowed access to the catharsis of vengeance?

I can’t help assuming there IS some greater narrative point, because I want there to be.

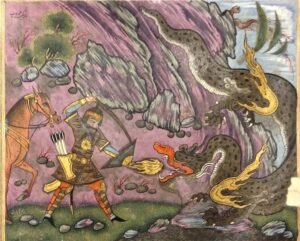

An illustration that shows Bizhan in the pit holding onto a rope. The hero Rostam is holding onto the other end and hauling him out while Manizheh watches. Six random hero dudes stand around together with two horses.

KE: I too was absolutely fascinated and delighted by the “disguised as merchants” trope. Two hundred years after Ferdowsi the Mongols sent spies disguised as merchants ahead of their line of conquest to check things out, so this means it’s not just a trope but a real aspect of historical espionage in this era.

I loved this episode in large part because it has an active woman character in it. Once again I am intrigued by the sexual politics on display in the Shahnameh because ONCE AGAIN it is the woman who is the sexually assertive one, the woman who approaches the man, who invites him to be with her. There is so much I could say about how the post-Victorian post-50s Puritanical culture of the UK and USA has warped the ability of readers steeped in those two traditions to conceive of sexual politics different from those we have been assured are traditional and inevitable worldwide. If a woman lives in something resembling a woman’s palace or women’s wing or a harem, etc, then it is also assumed she is a guarded virgin who is either too constrained or too passive and virginal to get up to anything. But, again, virginity is a particularist concept, not a universal one. Many societies simply do not valorize virginity even if they value women being faithful to their husbands, for example. And yet even Sudabeh is not taken to task so much (I think) for wanting to have sex with Seyavash but for her anger at his rejection and her efforts to lie about him and thus destroy him.

Look how often we have seen the female gaze at work in this story, even with the relatively minor roles women have played. Manizheh sees Bizhan and desires him: that’s classic female gaze right there. Her father’s anger seems directed at her defiance in sleeping with the enemy rather than any concern over her “purity.”

Again, notice how he strips her of her wealth, which makes it clear that these women controlled their own finances. Whatever constraints they lived under (and I’m not entirely sure of what those are as we have seen women traveling in earlier episodes in order to resolve conflicts) they were not dependent for their pin money on some man’s parsimonious doling out of a few coins here and there. Women’s financial and intellectual and physical dependence often seems like such a staple of British and USA Victorian and post-Victorian literature that it really delights me to see my expectations shattered to bits here, where Manizheh acts on her own desires, suffers the consequences, questions Rostam, and as reward is shown the respect she deserves.

Not sure who this image of a man and a woman in bed together represents but honestly it could be so many of the couples in the Shahnameh, so I will imagine it is Bizhan and Manizheh enjoying some well deserved canoodling.

I also was OUTRAGED that Afrasyab’s death is passed over in a synopsis. I assume this means it is written and that Davis just chose not to translate it. It’s just very odd to me too. Faragis’s flight is skipped over although surely it is dramatic, and now Afrasyab’s death when he has been the antagonist for so long. *sigh*

I also wish I knew more about the cultural aspects of forgiveness in this context especially since in other cases Rostam is unforgiving. So what and why now? SO MANY QUESTIONS. So far if there is one over-arching commentary it is that both good fortune and bad fortune are transitory compared to the inevitability of death. There’s a bit of the same tone as Ecclesiastes underlying this poem, perhaps.

Next week: The Occultation of Kay Khosrow

Previously: Introduction, The First Kings, The Demon King Zahhak, Feraydun and His Three Sons, The Story of Iraj, The Vengeance of Manuchehr, Sam & The Simorgh, The Tale of Zal and Rudabeh, Rostam, the Son of Zal-Dastan, The Beginning of the War Between Iran and Turan, Rostam and His Horse Rakhsh, Rostam and Kay Qobad, Kay Kavus’s War Against the Demons of Manzanderan, The Seven Trials of Rostam, The King of Hamaveran and His Daughter Sudabeh, The Tale of Sohrab, The Legend of Seyavash Pt. 1, The Legend of Seyavash Pt. 2, The Legend of Seyavash Pt. 3, Forud the Son of Seyavash, The Akvan Div