Join Tessa Gratton and me as we read the Shahnameh by Abolqasem Ferdowsi. We’re using the Dick Davis translation (Penguin Classics).

Today’s portion: The Legend of Seyavash (second of three parts, this part starting on page 237 and ending on page 259)

Synopsis: Seyavash moves to Turkestan to escape Kavas’s terrible decisions, making a home there and marrying into Afrasyab’s family.

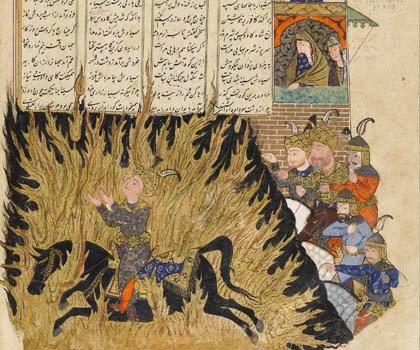

I suspect this scene of Seyavash facing Afrasyab across the Jihun River is for next week but it’s such a great image I used it this week.

TG: I am full of dread.

This middle section is basically Seyavash being awesome, while Afrasyab tries to be better than it’s in his nature to be (and constantly worrying that Seyavash will turn around and bite him someday), and Seyavash himself makes dire predictions about his destiny.

I’m so done with Kavus. Obviously. The nicest thing I can say about him is “at least he’s consistent in his terribleness.” It’s nuts that he makes Rostam look wise and level-headed. (And actually, with them side by side I suspect Rostam is supposed to be wise, generally good, but with the kind of temper that leads to being a total bad-ass on the battlefield, while Kavus is just temperamental and childish. Most of our looks at Rostam have been involving war and Kavus, the two things guaranteed to piss Rostam right off. The only other time I’ve sympathized with him was when he mourned so heavily for Sohrab.)

And speaking of Sohrab, I wonder if these stories are out of chronological order (assuming we’re right about that) because Sohrab is the ultimate doomsday version of father-son relationship, and Seyavash is forced into several father-son relationships here, and one (or all) of them is bound to go very wrong very soon. Kavus is his actual father, Piram and Afrasyab both sort of adopt him and take on a fatherly role, and of course we know but, like Rostam and Sohrab, neither Seyavash nor Garsivas knows that Garsivas is Seyavash’s actual grandfather or grand-uncle or something (and I suspect the downfall is going to start with Garsivas and jealousy).

Having the tale of Sohrab right before this one creates more tension for me than I might otherwise have had because of all the father-son talk. My dread just builds and builds because I both know how likely a terrible ending is, but also hope more strongly for a happier ending than Sohrab and Rostam got.

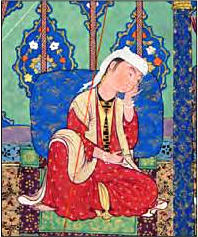

It is fascinating to me that Seyavash has personal knowledge of his impending doom! And he accepts it, even walking toward it. He doesn’t take Bahram and Zangeh’s advice because “the heavens secretly willed another fate for him.” At first I wondered if it was something he was aware of, or a coy narrator’s insertion. But later when the astrologers tell him not to build his city in Khotan, Seyavash basically has a breakdown about what he knows but cannot reveal, confessing to Piran that he’s not long for this world, but must accept his fate and enjoy life while he can. It’s obvious by then that Seyavash DOES hear God’s will or something like it, and accepts it even though it means his doom. It made me think of Gethsemane, and the tragic themes that come with a character knowing their terrible fate, but choosing to face it because of faith or love.

I wonder if the knowledge of destiny is related to his farr, and also if he’s taking warnings from God as inexorable destiny, instead of warnings for things to avoid! Maybe he got a little bad judgement from his father….

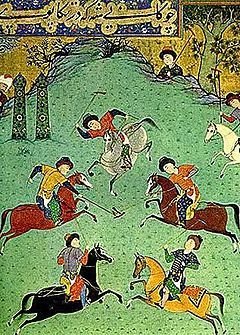

An illustration of playing polo, with five men on horseback (one a sixth rider partially obscured), with polo sticks.

KE: I too am in dread. Seyavash is clearly doomed, and I too am puzzled by his acceptance of his early death. I enjoyed the depictions of friendship between men, especially Piran and Seyavash, and the sense that he and Faragis have a reasonable marriage of mutual respect. This is the behavior I expect from the noble born if they are going to claim that their noble born ways are somehow superior, and yet they so rarely act this way!

After all this time putting up with Kavus just because he is king and descended from the right people, we get a person with actual farr, someone who acts for peace rather than war, and — naturally — he is not long for this world and destiny rolls against him.

I read Garsivas as his grandfather (or his great-grandfather? depending on if he is his mother’s grandfather or father). And yes, things aren’t looking good. The sense of impending disaster looms large.

And honestly: could Seyavash be any better of a YA hero? He’s practically perfect except for his passive acceptance of destiny, and even that is depicted as an aspect of his preternatural maturity and intelligence.

On to part three, which will doubtless break our hearts.

Next week: The final part of The Legend of Seyavash (page 259 to the end of the section)

*sob*

Previously: Introduction, The First Kings, The Demon King Zahhak, Feraydun and His Three Sons, The Story of Iraj, The Vengeance of Manuchehr, Sam & The Simorgh, The Tale of Zal and Rudabeh, Rostam, the Son of Zal-Dastan, The Beginning of the War Between Iran and Turan, Rostam and His Horse Rakhsh, Rostam and Kay Qobad, Kay Kavus’s War Against the Demons of Manzanderan, The Seven Trials of Rostam, The King of Hamaveran and His Daughter Sudabeh, The Tale of Sohrab, The Legend of Seyavash Pt. 1